Table of Contents

About the authors

| Joe Easterly Digital Scholarship Librarian University of Rochester |

| Kimberly Hoffman Head of Outreach, Learning, & Research Services River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester |

About the Tool and Class

| Title | Teaching Students to Explore Their Environment with Omeka |

| Tool | Omeka (omeka.org) |

| Tool description | Omeka is a web-based system for creating digital collections of media (especially images) and organizing them into exhibits. It allows multiple users to log in and edit the collection at the same time, facilitating project teams. Dozens of plugins exist which extend its functionality in metadata, mapping, video, and much more. |

| Class/Target Level | Secondary School Teachers, Post-Secondary Instructors |

| Course Title | Teaching with Omeka / Teachers In-Service Workshop, Memorial Art Gallery (MAG) |

| Background information about the class | The Instructors (Joe Easterly, Digital Scholarship Librarian) and Kim Hoffman (Head, Outreach, Learning, and Research Services), both from the University of Rochester River Campus Libraries were invited by the Memorial Art Gallery to present a workshop as part of its Teacher In-Service professional development program, which is targeted towards K-12 teachers and library media specialists in the Rochester area. The workshop took place in on a Mid-April evening in 2018. |

| Lesson time | 2 hours 30 minutes |

| Number of students | 45, divided into groups of 5 per table |

| Learning outcomes | Arrange (paper) elements of a sample art exhibit to develop the look, feel, organization, and primary research/audience focus in order to gain a sense of Omeka’s power as a tool without being bogged down (just yet) with technology Investigate several examples of Omeka projects that demonstrate portfolio and online exhibit applications in order tovisualize and brainstorm what projects they could create for their students and even across schools Apply new/missing authoritative tags and organize existing records into a sample Omeka project to develop collections within the greater project in order to internalize the mechanics and necessary skill sets/concepts needed to develop an Omeka project. |

Lesson Plan

Opening

Anticipatory Set (both verbal prompt and displayed via projector, while participants settled into their seats): As you journeyed to the Memorial Art Gallery tonight (from school, home), think back to any works of art that you passed on the way – considering your field, what would you might want to know about that art?

Body

In small groups (4-5 people per group) with a collection of materials printed out, participants browse through what they have and begin to make sense out of patterns they see in the materials. Should they organize by genre, by materials used, by location, by time frame, by artist, by overarching theme, etc.? In paper format on a table, the group lays out what the exhibit might look like and what the overarching research question might be.

Reflection from groups on how they organized, what was important, what terms did they use?

Sample questions to think about:

- What kind of metadata fields are going to be used in your collection?

- Are there any kind of information you wish was included, but wasn’t printed on the paper?

- How do you imagine your users interacting with your exhibit? What will they gain?

This work on paper will emulate

what they could do in Omeka . . .

Share page of resources (libguides.lib.rochester.edu/omeka) and advise participants that all of the content shown in the workshop is linked off of this guide.

What is Omeka? Who uses it? What are some reasons why people use it? Share one or two sample projects which showcase its capabilities, especially in terms of digital portfolios and exhibits. Emphasize Omeka’s modular structure: straight out of the box, it’s actually pretty bare-boned. Plugins are an essential aspect to its architecture.

With a search strategy in hand (e.g. “powered by Omeka” in Google), participants browse through search results to gain ideas of what Omeka can do, and brainstorm use cases for their classrooms. As participants collect examples and notes, they add their favorites to a shared Google Doc, linked off of the LibGuide.

Share out discussion within small groups and then to the entire workshop – sharing of ideas, concepts in Omeka that stand out, etc.

Introduce and highlight Omeka/Metadata jargon, such as Items, Collections, Dublin Core, Simple Pages, Exhibits

With their projects planned out on paper (at the beginning of this workshop), participants now will now build them out digitally using Omeka. Identifiers and other metadata were printed next to the images on those pieces of paper— students will now use them to locate the corresponding digital records in Omeka and organize them into exhibits.

When moving between groups of participants, field questions related to the “fancier” interactive components participants came across when searching for examples, and how they might be integrated.

Closing

Round up of takeaways, group discussion of ideas on how participants can incorporate Omeka into their teaching.

Assessment:

Assessment of learning objectives is continuous as the instructors move among the group tables, answer questions, and ensure that each group is on track to complete their activities. Another means of assessment is during the closing, when participants share ideas of how they might be able to incorporate Omeka.

Accommodation

For participants who have difficulty using computers, they can focus their participation on the paper phase of this activity and allow another group member at their table operate the laptop. More broadly, participants can meet much of the learning objectives by participating in discussion and looking on with other members of their groups.

Reflection

Reflection from Instructor

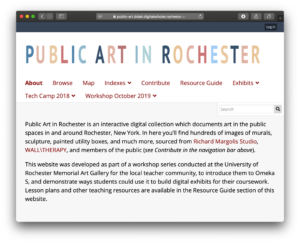

used for the workshop.

Image by J. Easterly, with permission.

Omeka heavily relies on its content in order for the tool to have a sense of structure. Omeka can be used to organize just about anything into a story, from manuscript pages and letters (dslab.lib.rochester.edu/esw) to field data of endangered languages (mcdonough.digitalscholar.rochester.edu). In order to teach with Omeka — especially in a single two-and-a-half-hour session — We had to prepopulate it with a reasonably-sized collection. Two of the very first questions Kim and I had for the MAG was “What subjects to these teachers teach? What level?” and their reply was “you never can tell, it varies from session to session.” Kim and I were stuck finding a digital collection that is interesting, didn’t require any background knowledge, and yet could still be academically useful. We decided on public art for those factors and more:

- It is usually rapidly accessible to viewers, by design

- Like all forms of art, it covers a wide range of subjects

- It often speaks to issues of local cultural interest

- It interacts with its immediate environment, neighborhood, and region. It is geolocatable and can be mapped.

One final factor is that public engagement is an essential aspect of Public Art. People are meant to comment on it, take pictures and share them. This mirrors the River Campus Libraries’ and the Memorial Art Gallery’s strategic goals around community engagement, and the public leadership local schools hope to instill in their students. Further to this, Omeka has a plugin which lets anyone, without a user account upload images and metadata into the system. This means that students could create a public engagement tool where students could collect data from their neighborhoods.

Our hope was that these intersecting factors would make it easy for any teacher — art, civics, history, science, math, elementary school, etc. — would be able to assemble the images into a compelling story and see how they could bring this tool back into their classroom.

Digital scholarship involves using a digital tool to accomplish something which could not be otherwise done with non-digital means. The tool plays an essential role in the research question and will likely cause that question to be adjusted due to the continued presence of the tool. Key to the design of this workshop was ensuring that the participants could experience this interaction, which also meant that they had to have a research question already formulated. We opted to have this question-building activity on paper so that they could think it through without also having to learn a new tool at the same time. For the participants who might struggle with technology, having a plan on paper also translates their work with the tool into a structured set of manageable steps with guaranteed success (e.g., search in this box for this image title, and then click Add to add it to the exhibit page, and repeat for the next image, etc.).

These strategies worked. The participants had lots of energy (even after teaching all day) and the discussion at the tables was vibrant.

Preparation time/materials

The Omeka website was built in its entirety ahead of time over the course of a month. The image collection—licensed from local photographers and a local public arts project, along with images contributed by the instructors— were added ahead of time using a CSV import plugin. In Omeka, metadata can be added not only to item records, but to the records for the image files as well. This made it possible to track the licensing information for a photograph of a monument taken by a professional photographer, and a photograph of the same monument taken by someone else.

Benefits and challenges of the tool

Omeka’s functionality can be extended in innumerable ways through its large library of plugins. It is especially good at creating interactive maps.

The server requirements for Omeka can be challenge. From an IT professional standpoint, they are very ordinary (in fact extremely easy to set up and administer), a teacher must have access to an IT department with a server in order to use Omeka as demonstrated in the workshop. Most do, but some don’t.

At institutions (such as the University of Rochester) which subscribe to Reclaim Hosting (www.reclaimhosting.com) or another CPanel-based shared hosting provider, it is actually really easy for faculty and students with limited technical skills to set up an instance of Omeka.

In-class experience

At times, the questions and discussion from the participants became more than the two instructors could handle, and a couple of “ringers” — colleagues from RCL and the MAG experienced with Omeka who were attending were able to fill in as needed.

The section of the lesson plan where I explained what Omeka is ran over by at least 15 minutes so we moved straight into the digital collection-building activity.

We were concerned (rightly so, it turns out) that students may overwrite each other’s work — let alone the fact that we didn’t have 45 laptops — so we required each group to designate a single person to operate the computer, with input from their fellow group members.

Ease of use/ranking

Beginner. While the skills taught are very basic, with such a large and diverse crowd, the instructor needs broad expertise in using Omeka to be able to successfully field questions from the participants.

Reflection from students

Evaluations from the participants were mostly positive, although they echo the issues mentioned in the sections above— they picked up on our improvised shift halfway through (where the Omeka explanation ran over), and reported that back as “could be more organized.” They also lamented the lack of computers, and an instance where two participants were confused because they kept overwriting each other’s work. Another two participants reported feeling completely lost. A handful of reviews were exuberant and shared how they plan to incorporate Omeka into their teaching.